Sand Studies

Every Saturday for the last six months I have risen early, dropped my son at the bakery at 8am and headed to the beach with my dog Luath.

Tentsmuir is an extraordinary combination of forest, dune, beach and water sitting between the Eden and Tay estuaries that is best appreciated early, before the people gather and while the sun is still rising low out of the North Sea.

I do a micro-triathlon – cycle to tire the dog, run to tire me then a dip in the sea to settle into the day.

Then the best part, that 2-mile dander among the sands and water, hearing the waves and the birds, absorbing the light and wind, and exploring the sands. Sometimes there is little beach and the waves roll near up to the dunes, on some low spring tides you can walk so far out you think you can see Denmark. Last winter there were days when all was frozen and it was like walking across the tundra.

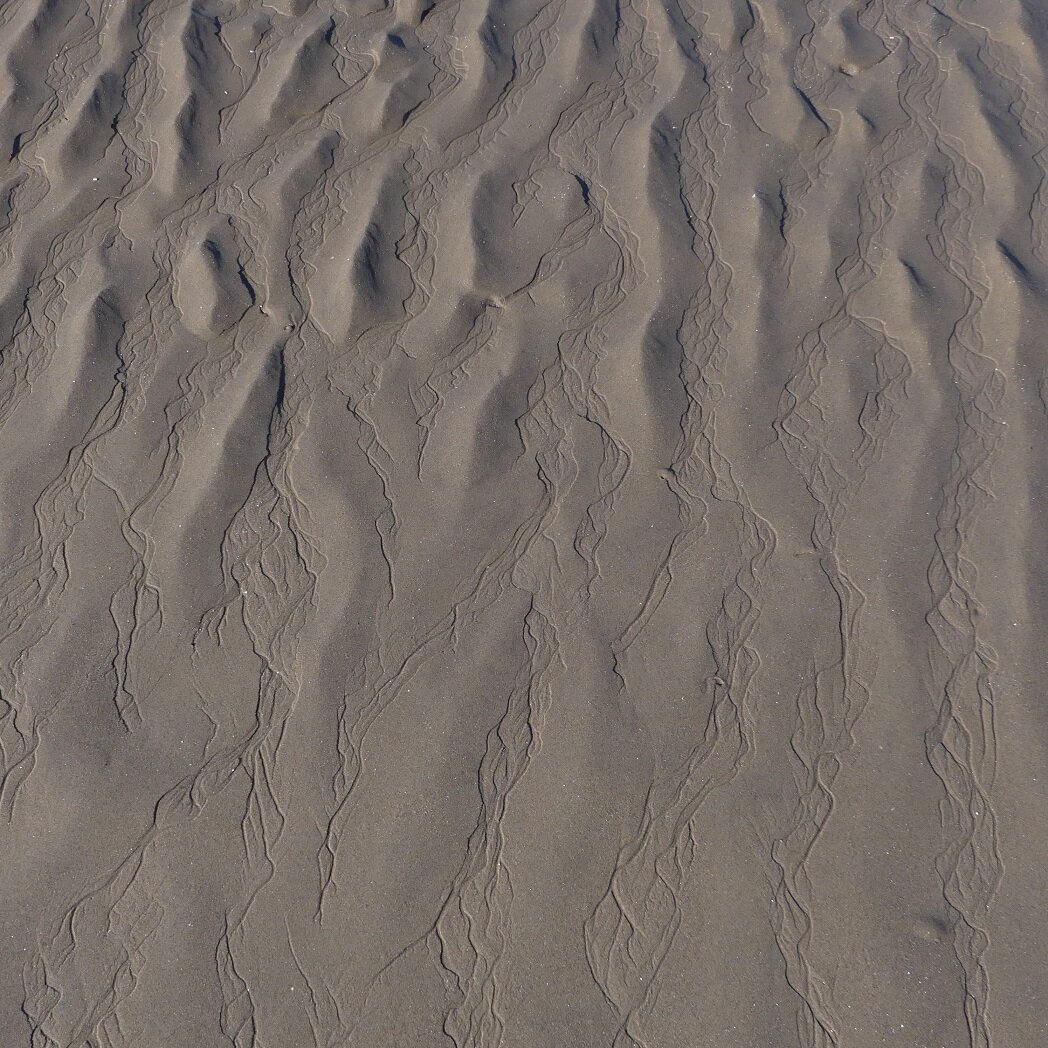

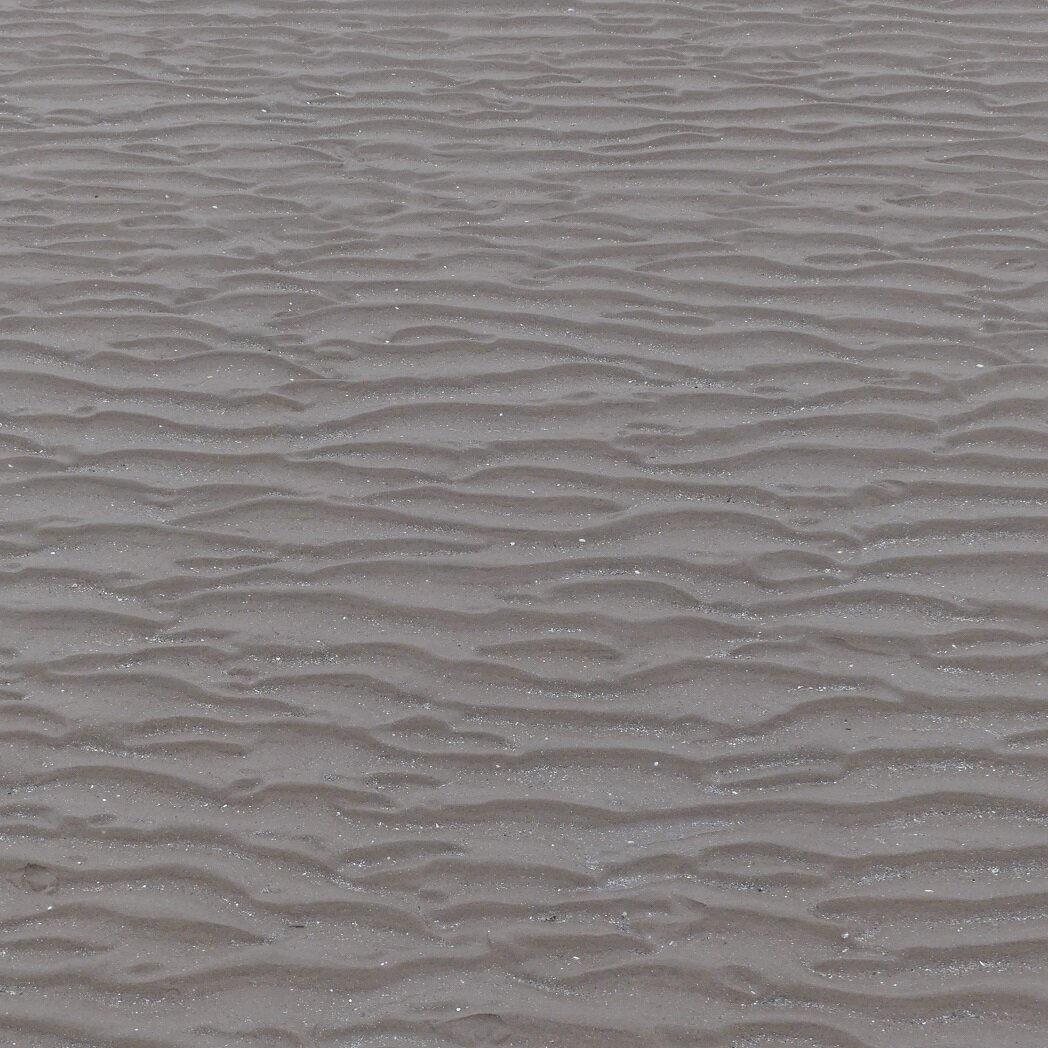

Every time the sand is different, varied patterns depending on wind, humidity, tide, rain, incline and grain size. And they appear different according to the strength of the light, its diffusivity through cloud or haar, light angle and mineral colour.

It is persistently astonishing how much variety is possible from small particles almost identical in size and colour. What breaks the monotony of its uniformity is its interaction with nature, being able to be blown around shifted and turned up side down. That is what creates the beauty.

I’m increasingly finding it’s the same for buildings – finding beauty in simple materials, natural patterns, weathered and well lit. The role of the designer is to create the stage, frame the shot and allow that to happen. Nature to reveal its beauty, us to not disturb it, and to look.

That walk is mesmeric, out of time, suffused in low light, all senses firing, ending with coffee and return to the world. It has helped me stay sane through lockdown.

There is sand too, near where we live. The Howe of Fife is a bowl of flat land where 10,000 years ago retreating glaciers drained vast quantities of ground up stone between the hard basalt of the Lomond volcanic stubs and the eastern tail of the Ochil hills. Industrial quarries now extract the sand and work their way through the fields, lowering them by 10m or more.

As the land sinks, so a mountain rises in their midst, as Fife Council’s landfill of waste piles high to challenge the Lomond paps. This is the tale of our time, eating out the natural resources and replacing them with waste, polluting the ground and the air. In pockets, the sands pits sit below the water table and flood to become biodiverse habitats, too static to reinstate the mutable wetland landscape of the Howe before it was drained for agriculture in the 19th century.

Sand is in crisis. Mankind’s second most consumed natural resource after water. We use it to make glass, concrete, the colour white and a huge range of the stuff we have an infinite appetite to make and consume. But, like water, it is a great example of a natural resource we treat as infinite and consume like there is no tomorrow. We squander this natural wonder, failing to value it and develop circular economy processes to sustain it as an industrial and construction resource, thereby protecting our planets beautiful natural sand landscapes.

Time flows like the tides and life’s patterns are constantly shifting. Our son Sandy (yes, that is his name) left school last Friday, quit the Bakery on Saturday and took a bus on Tuesday to a summer job on the Hebrides. Luath and I now seek a new Saturday routine to carry us through summer.

If you have enjoyed this blog, please read the wonderful book Sand Stories by Kiran Pereira.